Late in the 19th century Gottlieb Daimler and Karl Benz gave Germany the first motor cars. France displayed immediate enthusiasm for the new locomotion, but we Britons were rather backward. Agriculture, racing and hunting had made us the horsiest nation in the world. We were so passionately horsey that at first we even resented the advent of the pedal cycle. We sneered at its riders, calling them "cads on castors." We applauded our horsey benches for fining them for " scorching." Such a mentality found the pioneer motor vehicles still more offensive. They terrified our horses. They churned up towering dustclouds from water-bound roads innocent of tar. We pictured a day when crazy motorists would travel at railway speeds on public roads. So we thanked heaven that our statute book included an antique law —framed for huge steam traction engines —which compelled all self-propelled carriages to be preceded by a man with a red flag, and limited them to a maximum speed of four miles an hour. Against such prejudices our engineers found themselves temporarily helpless, and the British Motor industry consequently got away to a very poor start.

The Pioneers

Harry James had established a cycle manufacturing and light engineering works as far back as 1870, and had been among the first to build high-grade bicycles. His shrewd eyes instantly perceived the possibilities of the motor cycle. In 1901 he launched his first machine. There was already plenty of competition. Here are the names of some of his contemporaries at this time :—

Ariel, Aster, Barnes, Bat, Bradbury, Buchet, Butler, Chase, Clement-Garrard, De Dion, Dennis, Derby, Enfield, Excelsior, Hayward, Holden, Humber, Iris, Jap, Ormonde, Pearson, Pennington, Peugeot, Phoenix, Quadrant, R. & P., Raleigh, Rex, Riley, Singer, Swift, Vindec, Warner, Westlake.

It is significant that the majority of these names are forgotten except by veteran riders. Only three of them are still building motor cycles, though several others continue honourable records in the car and cycle industries. Darwin taught, that earth is the scene of an eternal struggle for the survival of the fittest! Natural selection would thus hallmark James as extremely "fit." The following brief analysis of his history will bring into clear relief some of the special qualities which enabled him to make good.

How James Began

In the early days no British maker designed or built his own engines. Knowledge and experience were alike lacking. The engines were necessarily purchased in lands where no arbitrary laws had tried to strangle progress. James was already an expert cycle builder, a good engineer, accomplished in machining good steels, not a mere assembler of bought parts. Too wise to run before he could walk, too conscientious to make his customers pay for his experiments, he bought the best air-cooled motor cycle engine available.

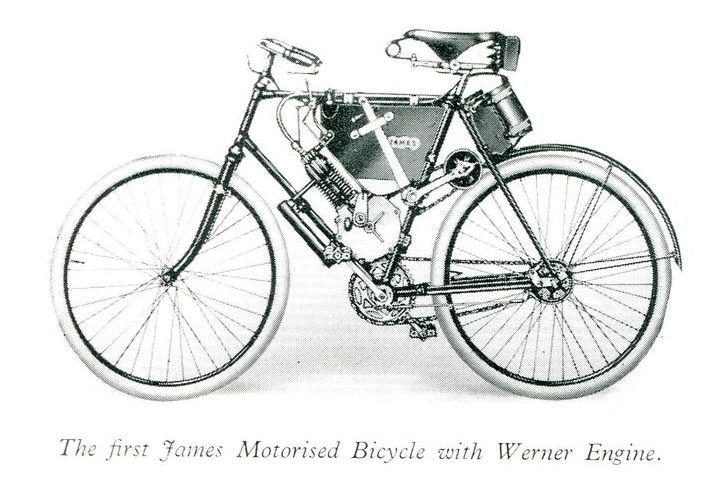

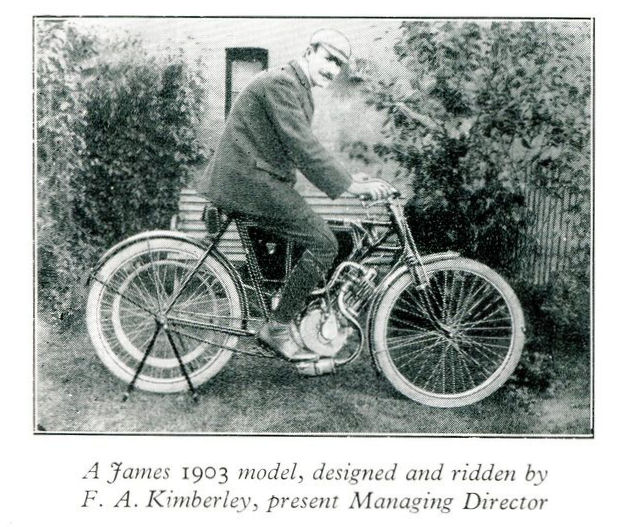

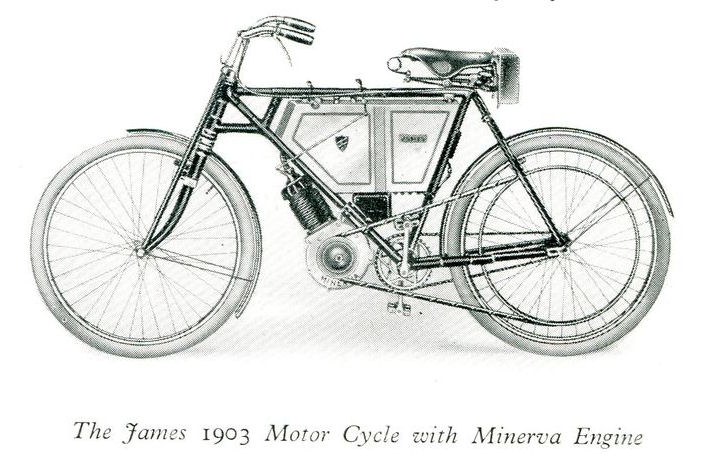

Two French brothers named Werner had produced in Paris the best motor cycle engine of the day. In 1902 James secured a small supply of these engines, and fitted them to reinforced bicycles of his own manufacture. In 1903 the Belgian firm of Minerva produced a better engine, to which James promptly switched —he always placed quality in the forefront. Both engines were good, but on the weak side. For 1903 Minerva marketed a more powerful unit, and James designed a still sturdier frame. From the first he had intended to become "All-British" as soon as possible, and this year he was able to give his clients the option of a British engine. This was a 2¾ h.p. single cylinder, with automatic atmospheric inlet valve, manufactured by the Motor Manufacturing Co. of Coventry.

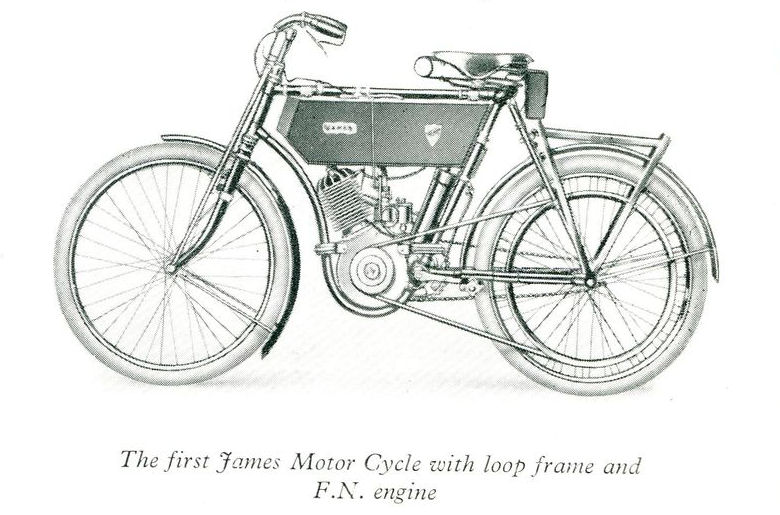

But all this time James was looking forward to making an engine of his own. There was no great hurry. Prejudice against motors died slowly, and sales as yet were modest. Caution was essential. 1904 found him still learning. He postponed making his own engine a little longer, preferring to fit a well-made unit by the Belgian Government small arms factory, under the name of F.N. (Fabrique Nationale).

Meanwhile, he was among the first to realise that a good engine required a firmer mounting than a couple of clips on the down tube of the frame — a method still utilised by many of his rivals. So he built the F.N. into the first loop frame ever made, an innovation widely copied all over the world to this very day.

The ideas underlying the conception of the first " all-James " motor cycle are worthy of study. By this time James knew the best and the worst of current designs. The best models of the period had many faults. All of them were uncomfortable, mainly owing to vibratory engines, crude forks, tiny saddles, and small tyres. All of them were notably weak on hills. In spite of a single gear and the manifold weakness of the belt drive at this time, a good rider could climb quite fair gradients, provided he got a good rush and a clear road. Moreover, any long or steep hill forced him to pedal very hard indeed, a fact which limited motor cycles to small saddles. The brakes of the period were poor, consisting of a flimsy rim-shoe on the rear belt pulley, and some weird, impotent improvisation on the rim of the front wheel. The high frames essential to strong pedal assistance, rendered machines unstable on grease. But all these defects were trivial compared to the frequency of tyre trouble. At the dawn of the motor era no nation had experience of heavier tyres than the light sections fitted to tandem pedal cycles. These were unequal to the weight and speed of motor cycles.

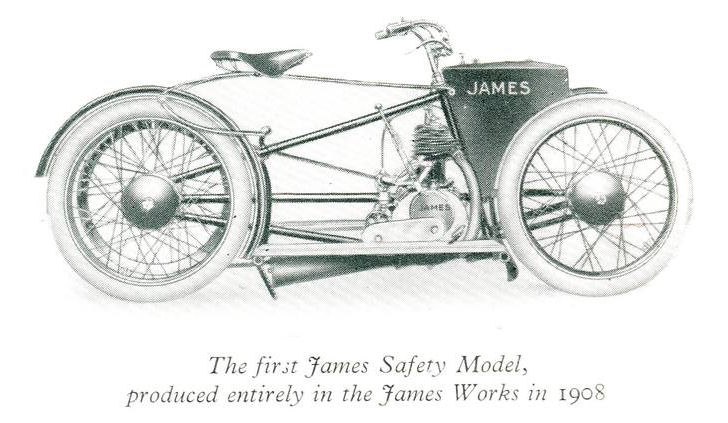

Strong measures were essential to save the new industry from premature extinction. James consequently essayed a clean break with the standards of the past. In co-operation with the late P. L. Renouf, an engineer and patentee of sound repute, he produced for the 1908 season the first complete all-James motor cycle.

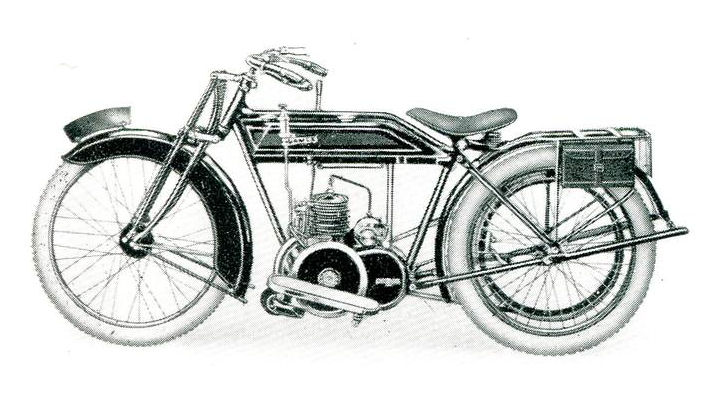

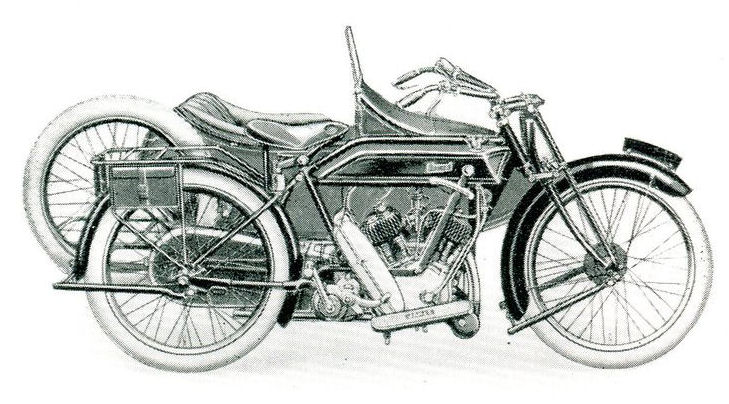

The James "Safety" Model

In the light of 36 years of subsequent development many holes can be picked in this design. James himself was not completely satisfied with it. He would have liked to add a variable gear, but there was no such device. He would have welcomed the tough modern tyres ; but no tyre company was capable of supplying them.

Nevertheless, the machine created a sensation for the accuracy with which it struck at the flaws in current design and indicated the trend of future development. An outstanding feature was the solution of the tyre problem. Both wheels were carried on " outrigger " spindles projecting from an open sided frame. Either wheel could if necessary be removed in a few seconds for tyre repair. If a puncture occurred, he could swiftly insert a new endless tube, and get the damaged tube vulcanised at his leisure. The abominated pedalling gear disappeared altogether. To compensate for the lack of pedal assistance, a large engine of 89 mm. bore was fitted.

Now that the pedals had gone, it was practicable to use a very low and stable frame. For the same reason a large and comfortable saddle, carried on a huge leaf spring with a damping device, became possible. The universal rim and tyre brakes were ruthlessly scrapped in favour of internal expanding types on both hubs — a system since universally copied. Comfort was further enhanced by the substitution of long footboards for the misery of the swinging pedals, which soon gave way to small footplates poised at a convenient angle. Incidentally, the engine design was notable in other respects than mere size. Its inlet valve was mounted inside a concentric, hollow tulip exhaust valve, permitting the kind of cylinder head later favoured by engineers then unborn. The inlet valve even had a variable lift for purposes of speed control. During three long years James painstakingly perfected this striking design.

The Conservative Briton

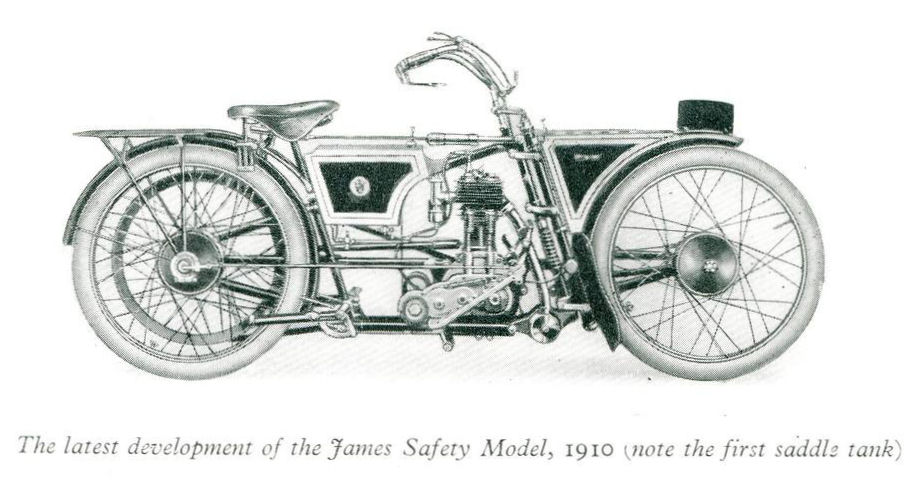

In retrospect James regards this amazing bantling with mixed feelings. Its unique features were mostly right and many of them have long since passed into universal practice —the sturdy engine mounting, low frame, abolition of pedal gear, footrests, internal brakes, detachable and interchangeable wheels, saddle tank, big saddle, spring suspension, central prop stand, etc. In the midst of so much pride James will, however, make one slightly rueful confession. He failed to recognise the innate conservatism of the average Briton ! We are slow to accept fundamental novelties. We plump for the orthodox.

The machine’s main handicap on the markets was the outrigger front wheel. Riders, as ex-cyclists, knew the best and the worst of the standard fork mounting. They fought very shy of a wheel supported on one side only. Moreover, just when they were beginning to understand conventional valve gear, they were scared of the Renouf valves.

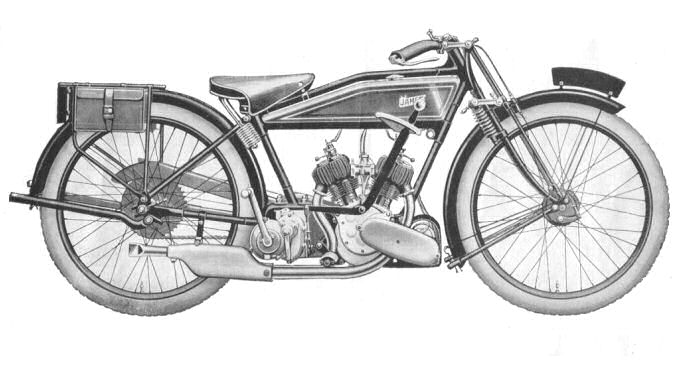

On the Bull

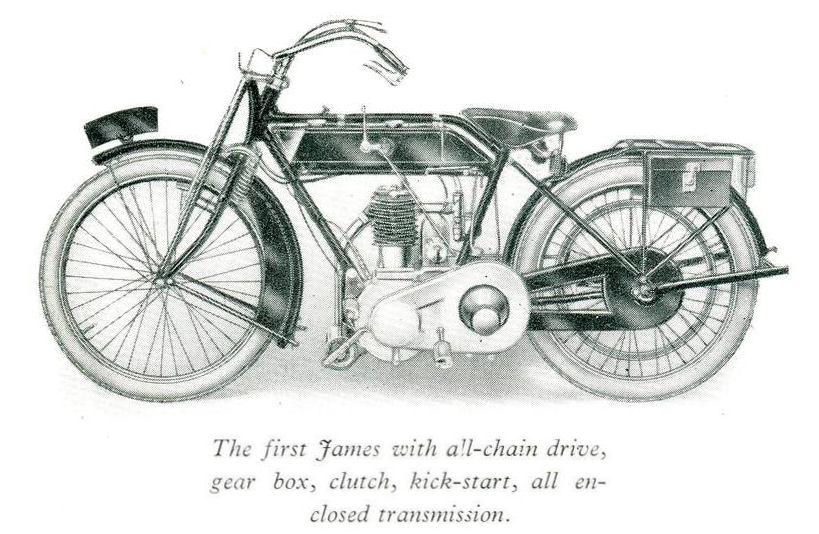

So in 1911 James saw the time was ripe for innovations of quite a different type. This time he paid due deference to prejudice and convention, whilst keeping a sure finger on the pulse of progress. In one stroke he outlined the future tendencies of the entire industry for many a long year. His new model was right on the centre of the bull— nothing less than the first all-chain drive, with separate two-speed gearbox, multi-plate clutch, kick-starter, a shock absorber for the final chain drive, and aluminium oil-bath cases for the front chain ! Alike in terms of specification and in the triumphant introduction of new features and the conquest of numerous obstacles, this model was a veritable tour de force.

Trouble Patch

The genius of this design may not be instantly apparent to some youthful observer, who cut his teeth on its later evolutions. But 1911 was a year of trouble for most manufacturers. It witnessed a sudden switch from the smooth, cushioning belt to the harsh, rigid chain. This alteration involved a host of serious pitfalls, which many engineers faced in too lighthearted a spirit.

The new rigid drive broke crankpins, fractured frames, accelerated engine wear, generated appalling vibration, snapped cycle parts, shook off minor fittings, disintegrated wire wheels, and robbed the road of its pleasure for many. James, who never allowed the public to tackle the testing which is the duty of a manufacturer, emerged from this ordeal with high credit. Indeed, his machine demanded but one alteration at the end of its first season, a modification not without real interest. On the original model the gears were housed in a malleable iron casting integral with the chainstays, to provide strength, maintain alignment, and relieve the user of a delicate adjustment. But if a duffer forgot to lubricate his gears, or was in the habit of muffing the gearchange, this construction created trouble. So James provided a separate bolt-on-type of gearbox, complete with multi-plate clutch, a kick starter, first with two speeds and subsequently with three.

The Boom Period

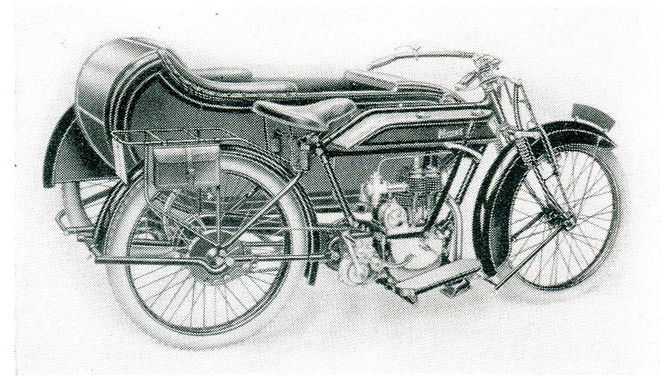

Next came a chapter demanding economic and political foresight as distinct from mere technical excellence. Reliability had been achieved. Hillclimbing had ceased to present any terrors. Bad weather did not affect the transmission. Design had stabilised. Firms who had fostered a delicate industry through its teething stages seemed about to reap rich rewards. The nation was extremely prosperous and the doors of four great markets stood wide open. First, the purely utility market of buyers who needed cheap personal transport. Next a growing export market with few limitations or problems. Third the sports and hobby demands. And fourth, the prosperous artisan who was eager to invest his surplus cash on a motor bicycle, and to add a sidecar after marriage. The motor cycle industry faced no real competition. The mass-produced baby car was still unborn. Second-hand cars were neither very cheap nor very good. A motor cycle boom was imminent.

" If you can keep your head "—

KIPLING.

In this novel atmosphere many makers surrendered to the wildest dreams. Overproduction, over-capitalisation and other economic blunders were rife. In all this excitement James kept a cool head. Again, in Kipling’s phrase he treated those two impostors, Triumph and Disaster, just the same. He saw that politically Europe was poised for a battle in markets. Roaring prosperity had not come to stay, and James did not go to the public for additional capital, nor turn out machines as one shells peas.

His policy was conservative. He kept his quality high, his prices reasonable, his customers happy, and restricted his output to a figure which entailed no jeopardy to honest workmanship. In the competition world, he liberally assisted those of his customers who enjoyed trials work. A few of his leading testers were trained to put his machines through such competitions as could teach the factory anything, and demonstrate his quality to riders, preferring the English and Scottish Six Day events, which used long distances, fierce hills and a close time schedule to prove reliability.

He disdained the larger ambitions in respect of speed. A maximum of 65-70 m.p.h., is fast enough for any reasonable person and this the James 3½ h.p. twin easily catered for. Fifteen or twenty miles an hour could easily be added, but the extra speed hoists prices, is apt to roughen a pleasant machine, and create prejudice.

Meanwhile he kept feeding the market as occasion suggested. About this time many firms introduced big singles, designed for particularly arduous solo or sidecar work. James made a famous 4¼ h.p. Big Single, which was docile and velvety. The reaction to these big singles was a demand for smoother engines, and out came one of the very pleasantest machines James has ever made —an exceptionally charming 3½ h.p. Vee twin, a gentleman’s motor cycle if ever there was one, which won golden opinions from all who rode it.

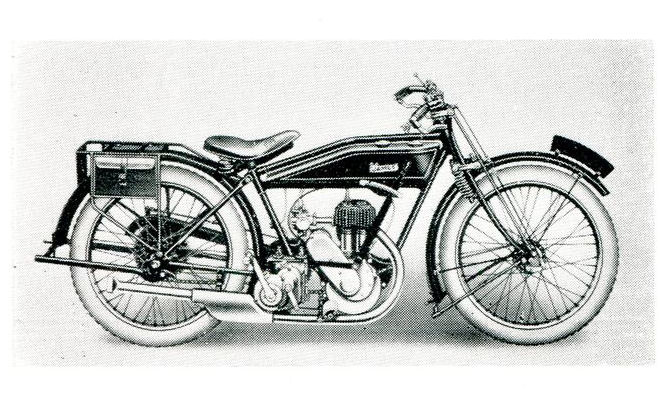

The First World War

On the brink of the first world war a certain revulsion against weight became apparent. Once again James assumed the mantle of the prophet, and flanked his tourist models with a new design destined to beget an innumerable progeny all over the world. His first 2¼ h.p. two-stroke Lightweight was no mere assembly of bought components, but the engine with its two-speed gearbox was conceived and built throughout in his own works, and displayed a quality and unity hard to parallel. The 1914-18 war choked private sales, and James was compulsorily switched into national service. For four years he could build but few machines for the general public, but concentrated on a special 5-6 h.p. dispatch rider’s model, produced to meet the special claims of the Belgian and Russian armies.

The Post-War Boom

The Armistice of 1918 confronted the motor cycle industry with a hectic situation.

Demobilised men were ready to pay fantastic prices. Costs had steepled — wages, machinery, materials were all very costly. Every factory wished to rush into production and reap a golden harvest, yet none had been able to prepare designs under the stress of war. British industry became a Bedlam for a year or two. Just as stability began to return in 1920, fortune struck James a cruel blow, for his entire motor cycle factory was burnt to the ground. Not until 1922 was he able to get going again. He signalised the occasion by marketing one of the very best 7 h.p. roadster twin-cylinders ever produced. Designed primarily for sidecar duties, it weighed no more than 325 lbs. though the specification included interchangeable wheels with clever quick-detachment devices, and aluminium chaincases. Its performance was exceptional.

Disappointment

Meanwhile the stage again seemed set for a tremendous boom. The industry emerged with credit from the difficult transition to peace conditions. Post-war motor cycles actually displayed far superior quality at less than pre-war costs. They dominated the international market by dint of sheer quality.

Gradually two most disquieting factors became apparent.

First, a network of currency restrictions and tariff walls began to hamper world trade.

Secondarily, the home market for motor cycles began to weaken with equal speed. Flow production of small cars had commenced. Their price gradually sank to round about £100 for the simplest models, and their quality was good. Thus, the used small car came into real and active competition with the new motor cycle, and seriously imperilled its sales to the adolescents of prosperous families. Simultaneously, the outlook for artisans became daily more gloomy, and few of them were in the mood to spend either wages or savings on motor cycles. In the teeth of such conditions, accentuated by export problems, the motor cycle industry was robbed of the golden harvest which had waved before its eyes for a few illusive moments.

Difficult Days

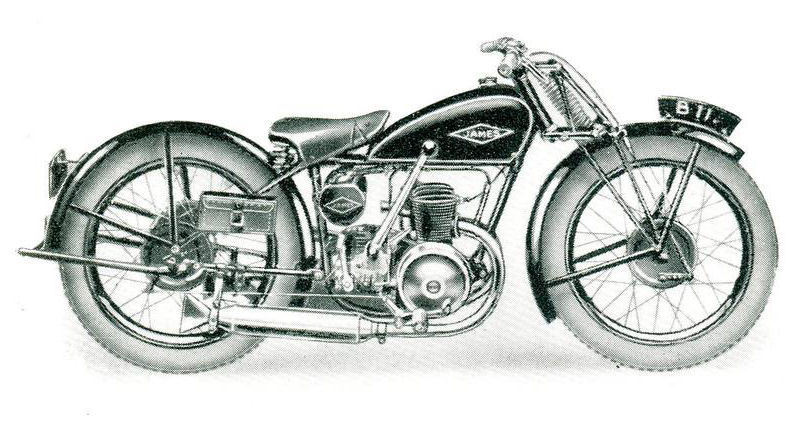

Nevertheless, whilst many factories put up their shutters and others became merged in larger concerns, James, as ever, kept his head. He fed the shrinking market shrewdly, producing from time to time some newer model well suited to the difficulties of the times. In 1923 his famous 350cc. won much kudos. 1924 saw the birth of a tough little 250cc. fourstroke. 1925 produced a fleet o.h.v. 350cc. model and so forth. In 1928, despite his thrifty expenditure on the sporting side, he enjoyed a truly remarkable run of competition successes. A year later his 500cc. o.h.v., twin was acclaimed and justified his policy.

James As A Prophet

1930-31 brought the disastrous world trade depression, the gulf out of which the Fascist and Nazi parties climbed on the difficulties of their people to world power. James realised that big sales of full priced, full-size motor cycles were impossible under such conditions. He began to specialise in the quality lightweight. As far back as 1921 he had tested the market with the first modernised " autocycle," a type which has since become immensely popular. In 1928 James had been one of the first engineers to recognise the high merits of the modern two-stroke engines, and set himself to build them into machines of quite special excellence.

A Vital Decision

Confident that his judgment was sound, James decided in 1936 to abandon temporarily the manufacture of costlier and heavier machines, and to concentrate on lightweights till times might mend. There was no sense in cutting the quality of the bigger machines as a makeshift scheme in an impoverished and shrinking market. So he catalogued four two-stroke models, ranging from £28 0s. to £37 10s. in price, and from 148cc. to 249cc. in size. These limits were planned so that he could remain loyal to his consistently high standards of first-class workmanship and fine materials.

This policy was rewarded on the outbreak of World War No. 2, when he received recognition from our Government. When war produced a call for airborne divisions, carrying their own light motor transport far afield by air, engineers convinced the War Office that a first-class lightweight was the ideal mount for troops in rough country. James, in company with one other famous factory of similar age and experience, was invited to build these 125cc. military lightweights, constructed with folding handlebars and footrests for compact storage in aircraft. Some day the story of their merits and achievements may be told in full. In the opening of the Second Front and in the Battle of France and in Holland they played a part worthy of the James heritage of quality.

Prospect

It is still too early to hazard even a wild guess at the immediate future of this ancient and honourable industry. Many of us nourish dreams, which pessimists discount as wishful thinking. Whatever happens, James will be ready. If the circumstances favour the comparatively inexpensive lightweight, his unique experience will be available. In the meantime, he has kept his knowledge of the faster, heavier and costlier mounts right up to date.

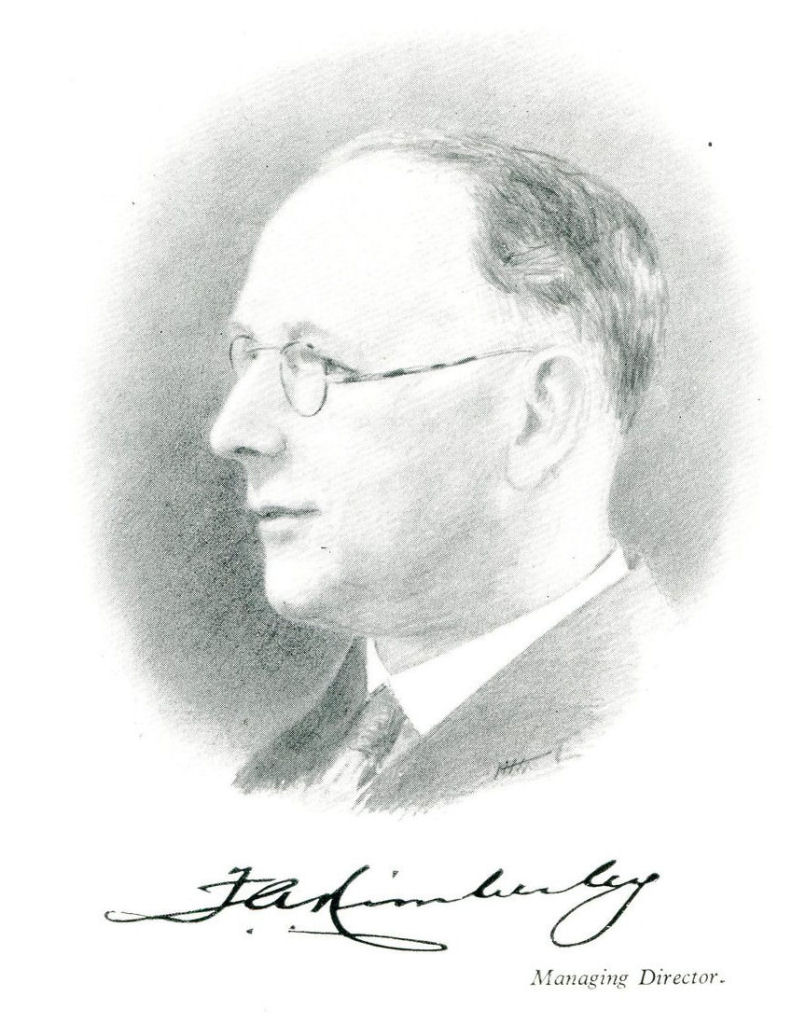

Where much is doubtful, one thing at least is certain. James is to-day a tough, battle-scarred warrior. He has survived many a stiff campaign, in which many of his old-time associates perished. His qualities— notably his sagacity, tenacity and foresight are unimpaired. His technical ability and engineering skill has been mightily intensified. The moral fastidiousness, which always forbade him to market anything shoddy, and his traditional adherence to quality is as firm as ever, and when at last our roads are reopened for civilian motoring, he will be ready with a range of quality machines, distinctive in design, dependable in service, which are comfortable to ride, as durable as honest craftsmanship can ensure, as speedy for their power, and as reasonable in price as conditions will allow.

B. H. Davies