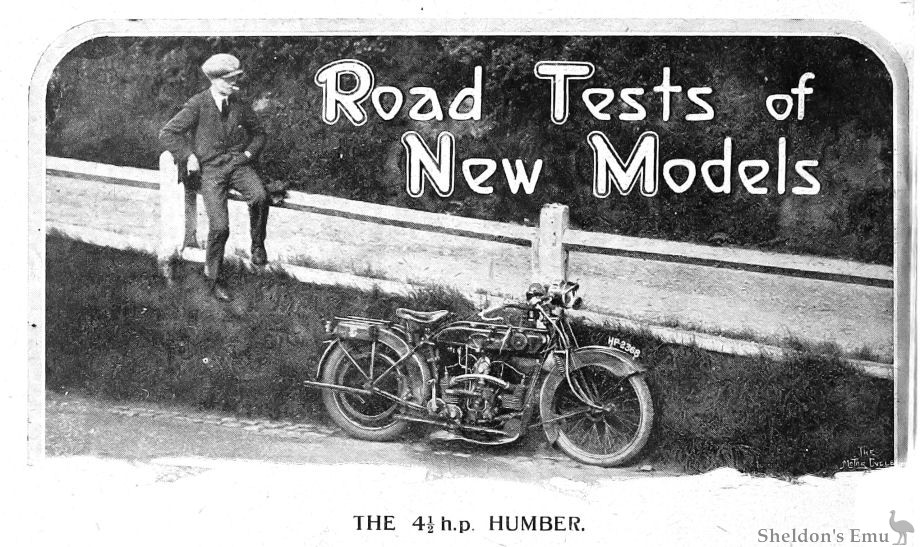

Road Tests of New Models - The 4½ h.p. Humber

The Motor Cycle JULY 14th, 1921.

SPECIFICATION.

ENGINE: 75 x 68 mm. = 700 c.c. flat twin.[1]

CARBURETTER: Claudel-Hobson.

LUBRICATION : Mechanical.

Hairpin cornering is a matter of great ease on the Humber, and although the footrests in this case are unusually high up, the balance of the machine gives one perfect confidence.

The 4 ½ Humber flat twin, a mount that answers splendidly as a double purpose machine. The engine, which has a bore and stroke of 75 X 68 mm., is particularly smooth, yet sufficiently powerful for sidecar touring in any district.

Note that the capacity given in this article is in error. A later article (14th Sept 1922) correctly states that the capacity is 600cc.

Bore/Stroke Calculator

THAT the 4½ h.p. Humber is a reliable and powerful mount has been amply proved by the results of this year's trials - particularly the stock machine event, in which it was one of those which gained a first-class award. How a machine behaves, however, and just how it would or would not appeal to the average buyer, can only be gauged after an actual test on the road. Thus it was with some interest that we seized an opportunity of a fairly extended trial of the latest Humber as a solo mount.

An Uneventful 400 Miles.

The test proved most successful, and seldom have we enjoyed as pleasurable a spell of riding. During 350-400 miles it never even seemed likely that the toolbag must be opened (nor was it), and a second or third kick never failed to start the engine.

The Humber cannot be regarded as a lightweight - it weighs well over 300 lb. fully equipped, the wheel-base is fairly long, and the riding position is unusually far back. However, it quickly proved as docile as any lightweight; indeed, possibly more so, and steadier. A single-lever Claudel-Hobson carburetter allowed the well-balanced flat twin to tick over, with the throttle lever in the shut position, so nicely and evenly that one could vault off the machine and walk alongside, controlling by one hand, when in second speed. This we demonstrated several times for the benefit of unbelieving friends.

Naturally, therefore, traffic riding in low gear became merely a matter of balance. And the balance of the Humber is excellent, so good at all speeds above 12 m.p.h. that one felt tempted to all sorts of acrobatic tricks. On grease, too, the same feeling of security prevailed, and, although some of our riding was over treacherously wet roads, there was a noticicable absence of any tendencies to skidding - "noticable" after two big singles minus efficient transmission shock absorbers! Possibly an inherent caution born of riding many mounts in all weathers saved us, but undoubtedly our wet-weather averages on the Humber were often as high as our normal dry-weather speeds on the same journeys.

No Vibration at Speed.

Regarding maximum speed, it is sufficient to say that there are few touring motor cycles on the road to-day that are appreciably faster than the machine under review. At full throttle there . is the same absence of vibration that is so pleasingly evident touring speeds.

Both the potterer and the hard rider will find that the engine is apparently quite tireless; it runs with just as little effort at the end of a 200 mile jaunt in the first ten miles. Indeed, like the luxurious car, its speed is inclined to be deceptive, and a speedometer is almost a necessity for the rider who would keep within the law !

Gear changing required very little practice, and the second neutral position in the gate (next to top) proved very convenient more than once, especially so the clutch, delightfully delicate in engagement, was inclined to drag very slightly. With footrests the pedal for the rear brake seemed too far forward for comfort, but the rider soon finds that he can fling his feet (?) about indiscriminately without fear of wobbling implications. The brake itself - acting a dummy belt - is amply powerful but the machine slows down so well on the throttle that it is seldom necessary to use it.

Hill-climbing Capabilities.

Edge, a well-known Midland test hill, which not all 4½ h.p. solo mounts surmount in top gear was climbed, with due respect for a wet road, at a speed which never dropped below 22 m.p.h. - according to Bonniksen - and al1 the way up the gradient on the highest ratio.

On a sixty-mile run at a good average speed fuel consumption worked out at approximately 75 m.p.g.; but the engine was not spared.

Of course, the most distinctive, and almost proverbial, feature of this machine is its silence. So well known is this quality even, and perhaps especially, to the man in the street that it does not seem necessary to emphasise it. Very, almost lamentably, few other makes deserve to be classified with the Humber in this respect.

Although the photographs in conjunction with the opening specification should serve to refresh the reader's memory regarding the general design, a few words on some of the mechanical features may not be amiss.

Oil in the crank case sump normally keeps the engine lubricated, but there is an auxiliary drip feed for emergency use. We found that, however much the engine was flooded with lubricant, there was no tendency to oil up the plugs, nor did there, on the other hand, seem to be any overheating when the drip was entirely shut off. The oil tank, by the way, is a separate cylindrical compartment set across and inside the main petrol tank. An ingenious assembly permits the valves, complete with their seatings and manifolds, to be removed without disturbing the cylinder.

Mudguarding is good, and, as a further protection, there is a large undershield, extending beneath the power unit.

Source: The Motor Cycle

See also Humber 1921 Models