Notes on the Construction and Performance of the 350 c.c. Single-cylinder Bradshaw Engine.

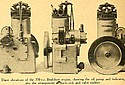

Three elevations of the 350 c.c. Bradshaw engine showing the oil pump and indicator, also the arrangement the push-rods and valve rockers.

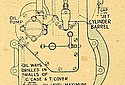

Lubrication diagram, showing the lead from the oil base to pump and from pump to annular recess surrounding the cylinder barrel.

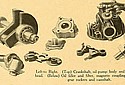

Left to Right. (Top) Crankshaft, oil-pump body and cylinder head. (Below) Oil filler and filter, magneto coupling, timing gear rockers and camshaft.

In the minds of one section of motor cyclists there appears to be some mystery in connection with oil cooling. If these notes succeed in dispelling such notions they will, at any rate, have accomplished a part of their object, for the 350 c.c. Bradshaw engine is as simple and as straightforward a piece of mechanism as can be imagined.

Strength of Construction.

As far as the working parts are concerned, the engine is normally and even massively constructed as regards wearing surfaces, though the reciprocating parts are kept as light as possible consistent with reliability. A stiff one-piece crankshaft with integral balance weights runs. in plain bearings with an additional double row ball race on the driving side. The big end is split horizontally, and the short aluminium piston is fitted with a scraper ring in the skirt which plays an important part in the functioning of the cooling system. Both valves are mounted in the detachable cast-iron head, and are inclined towards the centre of the combustion space. Valve operation is by means of a short stiff camshaft having two separate cams, through suitable rockers and adjustable tubular push rods.

Apart from the scraper ring on the piston, which is common on most car and aircraft engines, the only additional working part to the normal motor cycle engine is the simple valveless rotary plunger type of oil pump driven from the spindle of the magneto gear wheel, the magneto itself being carried on a platform directly behind the cylinder and driven through a simple coupling.

Oil Cooling System Described.

Now for the features which are responsible for the neat but somewhat unusual appearance of the engine. The cylinder consists of a simple cast-iron barrel having a flange at the upper end. This barrel is sunk into a cylindrical extension of the aluminium crank case, and is held therein by the cylinder head holding-down bolts, the walls being well clear of the surrounding case except for a collar at the top. The action of the combined lubricating and cooling system is simply this. The capacity of the oil pump (5.1 pints per minute at 2,000 r.p.m.) is very much greater than is necessary for the lubrication of the working parts, and the oil is led direct to an annular chamber surrounding the top of the cylinder barrel. From the lower edge of this space the oil is allowed to escape downwards over the barrel, and is then thrown all over the inside of the engine, including the walls of the cylinder and crank case, finally returning to a well in the engine base to be circulated again.

During its continuous circulation from and to the sump, the oil absorbs heat from the working parts, a proportion of which is dissipated through contact with the aluminium walls of the crank and cylinder case. It is therefore obvious that a large wall area is desirable, since there is no external oil radiator — in fact, there is not even an external oil pipe to leak or fracture from vibration. Everything about the oiling system is simple, and it is practically impossible for trouble to occur; - if, however, there is a shortage of oil, an indicator on the pump at once gives warning of the trouble.

A Quart of Oil in Circulation.

It is impossible to over-fill the oil sump, which holds 2.4 pints, owing to the position of the filling cap .at the correct oil. level, and the pump should be everlasting, since it operates under ideal conditions and is of the simplest construction, having no spring-loaded valves.

Through the courtesy of Mr. Gilbert Campling, of 90, Jermyn Street, W.1, we have been able to handle a standard production engine on the road, and our tests were spread out over several days so as to obtain a fair idea of the engine's capabilities in normal use. Details of the experimental frame in which the engine was fitted are unimportant, since it is not intended for the market. Suffice it, then, that it was fitted with a clutch and two-speed gear having a top ratio of 5.5 to 1 and all-chain drive with no shock absorber ; a Claudel-Hobson single-lever carburetter supplied the mixture.

After our initial experience — or rather inexperience : no kick-starter was fitted and the carburetter was inadvertently over-flooded — the engine invariably started easily, and throughout our test ran smoothly and faultlessly.

Impressions.

When the oil well is quite full there was a slight tendency to smoke when starting up or after descending hills with the throttle closed, but we had been warned when taking over the machine that the scraper ring fitted to this particular engine was imperfect. In spite of this slight tendency to smoke, however no plug trouble was experienced. Noise from the overhead valve gear is considerably less than that from many side-by-side valve units, and the power is beyond dispute.

A figure in the neighbourhood of 45 m.p.h. (by speedometer) is attainable on ordinary roads and one can fly up hills of 1 in 9 to 1 in 10 at well over the legal limit. In short, our experience goes to prove that the 350 c.c. Bradshaw is an engine to be reckoned with, and that it is capable of holding its own both in touring and competition fields. We look forward to a closer acquaintance.

The Motor Cycle May 11th, 1922. pp 598, 599.